Design has the power to guide, persuade, and sometimes mislead. As designers, how do we know when we’ve crossed the line between influence and manipulation?

As a designer, I’ve always been fascinated by how design intersects with psychology, especially how brands use visual cues and emotional triggers to influence decisions. I vividly remember a marketing lesson I attended as a child, where we explored a grocery store and learned why everything from the store layout to packaging design is deliberately crafted to guide our choices.

Supermarkets, for instance, are masterclasses in environmental design: no windows, no clocks, soft music, bright floors, all curated to keep us browsing longer. Products are placed strategically: premium goods at eye level, budget items above or below. Packaging speaks directly to different demographics. Even now, years later, I often find myself wandering the aisles just to observe how design influences my own behaviour.

But this curiosity has also made me question the ethics behind it all. When does influence become manipulation? Can we, as designers, manipulate for good? And if people were aware of how often they’re being nudged, would they make different choices?

The power designers hold

The power of design lies in its ability to work almost invisibly. We don’t always read the label, but we do notice the glossy finish, the clean layout, the subtle colour palette. These cues help us make snap judgments in a world overflowing with options. With an average of 35,000 decisions per day, we rely on mental shortcuts or heuristics. Good design offers clarity, but bad design can exploit those shortcuts.

Designers learn how to tap into this psychology. We understand how certain fonts can build trust, how colour combinations can evoke emotion, and how layout can suggest premium quality. That knowledge is valuable, but it also brings responsibility. If we use it purely to push products, regardless of what’s inside, we risk betraying the very trust we aim to earn.

As creatives, we hold the ability to shape perception, to make people feel something, believe something, want something. We do this using well-established psychological principles like: emotion-driven decision-making, visual hierarchy, the power of contrast and colour, and all sorts of cues that work quickly and often subconsciously. That’s not inherently bad. In fact, helping people cut through noise and make confident choices is one of the most valuable things design can do — as long as we’re using those tools with integrity.

Where influence turns into manipulation

Design, at its core, is about influence. Whether we’re encouraging someone to choose one brand over another, or guiding them through a digital interface, we’re constantly shaping perception and behaviour. That’s part of the job, and when done transparently, it’s a service. We help people navigate complex choices, cut through visual noise, and connect with products or ideas that are genuinely relevant to them.

But influence is powerful, and with that power comes the potential for misuse. The same design tools that build clarity and trust can also be used to obscure, distract, or pressure. This is where manipulation begins to emerge, not because of the tools themselves, but because of the intent behind them.

One framework I’ve found helpful comes from a video by John Mauriello for Design Theory, where he makes a powerful distinction:

Manipulation is influencing someone for your benefit, without their consent. Education is influencing someone for their benefit, with their understanding. And you want to educate, not manipulate.

This is the lens through which I now try to assess every project I work on. It’s not about avoiding persuasion, persuasion is natural, even necessary. But it’s about whether we’re being honest about what we’re persuading people towards. Are we giving them enough context to make a choice they’d stand by if they had all the facts?

It’s a subtle but powerful difference. Both education and manipulation can use the same visual tools: storytelling, typography, colour, emotional framing; but one empowers the person to make a decision they’ll feel good about, while the other nudges them toward an outcome they might later regret.

When doctors sold cigarettes

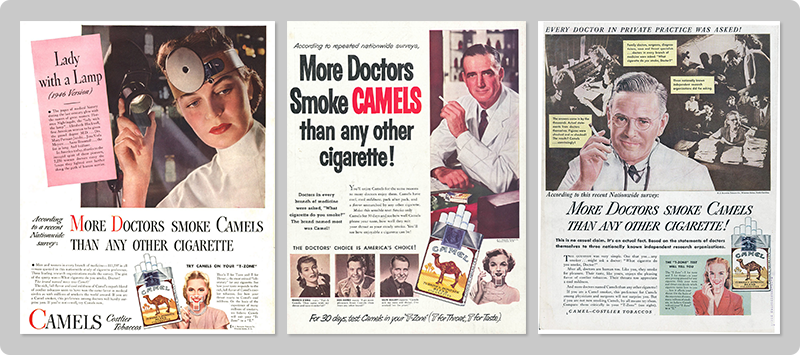

This isn’t just a modern concern. One of the clearest examples of deceptive design and messaging comes from the 1940s, when Camel cigarettes ran TV and print ads claiming, “More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette.” The visuals featured physicians in white coats, often mid-examination or with a stethoscope around their neck, calmly lighting a cigarette. The design of the advert leaned heavily on symbols of trust and authority, creating a false sense of safety and reassurance.

At the time, growing medical research was already pointing toward the dangers of smoking. Yet the ad campaign intentionally blurred that reality, using design and marketing to manipulate public perception in the brand’s favour. It’s a classic and widely accepted example of how visual cues and emotional storytelling can be used not to clarify, but to distort.

Where’s the line?

While we may no longer be designing cigarette ads, the ethical dilemmas we face today are just as real, though often more subtle. Rather than bold, misleading claims, modern manipulation often comes through exaggeration, omission, or carefully crafted visual cues that imply benefits which don’t truly exist. The visual language of trust is still being used, just in sleeker, more sophisticated ways.

Many persuasive strategies in marketing, like scarcity, social proof, or reciprocity, aren’t inherently unethical. They become problematic when used deceptively. A “limited offer” that isn’t really limited, fake reviews to simulate trust, or free gifts meant to pressure rather than delight, these all move us into manipulation. These tricks work, but they work because they exploit trust.

When used with care, these tools can be helpful. Real reviews, transparent information, honest scarcity — they inform, not mislead. They help the customer make a choice that feels right to them.

But the ethical challenge begins when the intention behind that influence shifts. When we stop thinking about what’s best for the user and start focusing only on what benefits the business, we risk crossing a line. That’s when influence becomes manipulation.

That line might seem blurry in practice, but intention matters. Take the Volkswagen emissions scandal as an example. For years, VW marketed their “clean diesel” vehicles as environmentally friendly, using sleek design and eco-conscious branding to support the claim. But behind the scenes, the cars were fitted with software designed to cheat emissions tests — emitting up to 40 times the legal limit of nitrogen oxides in real-world conditions. What looked like responsible, innovative design was, in reality, an intentional misrepresentation — one that misled regulators and customers alike.

Some visual enhancements are clearly symbolic or stylistic — they don’t deceive, they add to the emotional appeal. A Ferrari wouldn’t be a Ferrari without its dramatic curves, even if many design elements aren’t strictly functional. But the trouble starts when a product pretends to be something it’s not.

Design with intention

As designers, we know how to create emotional reactions. We know how to draw the eye, how to build trust visually, how to signal authority or urgency or exclusivity. The ethical question isn’t can we do it — it’s should we? And more importantly, why are we doing it?

That’s the point where intention meets responsibility, and where design becomes not just a tool of commerce, but a matter of integrity.

I try to ask myself regularly: Am I helping someone make a choice they’ll feel good about later? Am I being clear, not clever? Are we using design to communicate or to confuse?

Ethical design doesn’t mean neutral design. It means honest design — work that respects the person on the other side of the screen, the shelf, or the app. It means using our skills not just to persuade, but to empower.

Because design is influence. But influence doesn’t have to be manipulation. When we choose empathy, clarity, and transparency, we build something much more lasting: trust.

Share this article

Recent Posts

Empathy-led design thinking is strengthened by an understanding of real human behaviours, emotional responses, and diverse needs, rather than relying on simplified or fictionalised personas.

Learn important tips and valuable insights from my experience as a graphic designer to help you become successful in your creative journey.

Resources

Free Graphic Design CV Template

Provide prospective employers with a glimpse of your skills and demonstrate your design mastery using my captivating graphic design resume template.

Blog

Next article

Having multiple versions of the logo can help elevate a brand presence and ensure seamless consistency across every platform and medium.